Writer

Nearly fifty years after leaving her native Israel, author Linda Dittmar returns with an American friend to tour the places where she lived and visited as a child. When she stumbles upon the ruins of an abandoned Palestinian Village she is faced with a past that sits uneasily with her childhood memories—and the history she was raised never to question. That past is the reality of the Nakba, inscribed in rocks and mud, pine forests and parched summer grass, and the vibrant modernity that rises amidst the derelict sentinels of its past.

Nearly fifty years after leaving her native Israel, author Linda Dittmar returns with an American friend to tour the places where she lived and visited as a child. When she stumbles upon the ruins of an abandoned Palestinian Village she is faced with a past that sits uneasily with her childhood memories—and the history she was raised never to question. That past is the reality of the Nakba, inscribed in rocks and mud, pine forests and parched summer grass, and the vibrant modernity that rises amidst the derelict sentinels of its past.

Tracing Homelands; Israel, Palestine, and the Claims of Belonging

Olive Branch Press, an imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc. (Summer 2023)

An intimate account of a journey that surfaces inconvenient truths, Tracing Homelands is about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—truths that are often buried in silence. Its uniquely personal voice charts the author’s reluctant journey to uncover the ruins of Palestinian villages destroyed in the 1948 war, while weaving flashbacks to her Israeli youth. Along the way she is faced with a growing awareness of the Palestinians’ loss of homelands as the Israelis claimed theirs. The book’s underlying thread is also an inquiry into silence and myopia and how the land itself speaks its own truths.

An intimate account of a journey that surfaces inconvenient truths, Tracing Homelands is about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—truths that are often buried in silence. Its uniquely personal voice charts the author’s reluctant journey to uncover the ruins of Palestinian villages destroyed in the 1948 war, while weaving flashbacks to her Israeli youth. Along the way she is faced with a growing awareness of the Palestinians’ loss of homelands as the Israelis claimed theirs. The book’s underlying thread is also an inquiry into silence and myopia and how the land itself speaks its own truths.

First conceived at a workshop offered by UMB’s William Joiner Center for the Study of War and its Social Consequences, Tracing Homelands was supported by generous residency fellowships at the Women’s Study Research Center at Santa Fe, at the Santa Fe Art Institute, and at the Vermont Studio Center.

Recent Reviews of Tracing Homelands

“Their blood cried out—Israeli-American’s memoir faces the Nakba,” Steve France, Mondoweiss, July 11, 2023.

“[A] highly engrossing and original exploration… poignant and multilayered,…” “resonant,” “unflinching,” and yet “soft spoken.” “[In it] she has served as a kind of palimpsest…allowing the Nakba reality and the Nakba narrative to overwrite but not erase her Israeli reality and Narrative.”

“A Land without People for a People without Land?” Louis Segal, Hoot, Friends of Piedmont Avenue Library. Vol.8 #2, November 15, 2023.

“Elegant and lyrical,” “warm and … painfully honest,” “a literary tour de force, a subtle love song, a sensual feast of the landscape.” “Tracing Homelands is an ode to memory, to compassion, to quiet inquiry and to existential reflection on how to live or act in, and heal, our cruel, crazy, and beautiful world.”

Tracing Homelands; Israel, Palestine and the Claims of Belonging, Ida Audeh. Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, November/December 2023

“… a beautifully written memoir…penned as a forensic exploration.” “One has to admire Ditmar’s unflinching honesty.”

“An Israeli American revisits the Palestine of her Youth,” Joann Mackenzie, The Gloucester Times. December 6 2023. Israeli

“… A woman of 85 remembering the young woman she was, and poignantly revisiting the places of her childhood, which were home to Palestinians who are no longer there.”

Tracing Homelands; Israel, Palestine, and the Claims of Belonging, Kevin Murray, Good Reads, January 3, 2024.

“Part memoir, part travelogue, part reporting,… part confession, the book cannot help but capture anyone’s interested in the tragic history of this land…. Yes, the book is timely, by no intention of the author… “one woman’s painful quest to understand the roots of the current crisis in her own experience and in the land on which she and her family walked… and continue to walk.”

“Palestine, Oh, Palestine!” Paul Buhle, Monthly Review, Vol.75 No.8, January 2024.

“A brilliantly written, tragic pondering of the Palestinian fate, page by page, but also a hard look at the assumptions that made even the best-intended Zionists avid, if sometimes unknowing, partners in the large scheme of dispossession.” “Wonderfully descriptive prose… priceless glimpses…”

“Israel, Palestine, and the Claims of Belonging” Inez Hedges, Socialism and Democracy, Vol.24 No.1 (March 2024).

“Brilliant and challenging,” “strikingly original,” “seamlessly carries the reader along,” “An open and honest account… Dittmar takes us on a journey that can lead us toward a better understanding of history and ultimately guide us toward a more promising future.”

Selected Past Book Tour Events

- Palestine Museum, interview, August 13, 2023. With Faisal Saleh and Christa Bruhn.

- Launch at the Cambridge Friends’ Meeting House, September 28, 2023. Sponsored by JVP, the Workers’ Circle, If Not Now, and the Alliance for 1for3 Water Justice.

- Publisher’s launch, October 11, 2023. Sponsored by Interlink Publishing; Middle East Peace and Justice Coalition, UMass Institute for Holocaust; Genocide, and Memory Studies; UMass students for Justice in Palestine; and others.

- Consequence Forum, interview with Martha Collins, October 23, 2023.

- Old Cambridge Baptist Church, December 3, 2023. Sponsored by the Adult Education and Formation Team.

- Glaucester (MA) Writers Center, December 7, 2023.

- Community Church of Boston, December 11, 2023.

- Praxis Peace Institute, interview, January 12, 2024.

- World beyond war book club, January 11-February 1, 2024.

- Santa Fe Art Institute, February 13, 2024.

- Rainbow Lifelong Learning Institute, course, March 5-April 2, 2024.

- Brookline Peace Coalition, March 2, 2024.

- Munroe County (FL) Public Library, March 6, 2024.

Published chapters from Tracing Homelands

- “The Clearing,” The Massachusetts Review, March 2021, pp.46-58.

- “A View from the Minaret,” Harvard’s Divinity School Bulletin, Spring/Summer 2019, pp.32-40. (bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/spring-summer-2019)

- “Tantura,” Consequence, Vol. 10, 2028, pp.194-202.

- “Aqir,” Finalist in Nowhere Magazine, 2018

- “Points of Departure,” Jewish Currents, 2017, two installments.

- “Stories Stones Tell,” Shifting Sands: Jewish Women Confront the Occupation. Ossie Gabriel Adelfang Ed. Whole World Press 2010, pp.1-12.

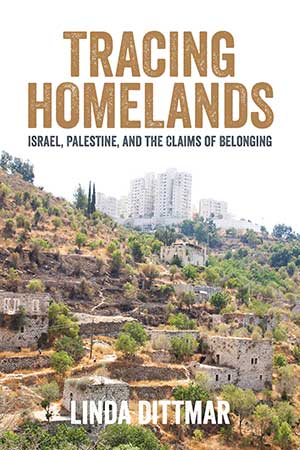

Bir’im Arch. Photo: Deborah Bright

An excerpt from the book. . .

Over our four years in Israel, what we saw of demolished Palestinian villages mostly varied in details: the arch of a doorway, the smell lingering in a wall, a clay oven still stained with smoke—variations on a theme. Now back in my American home, I feel the cumulative weight of the Nakba. Included are not only memories, but intimate tactile reminders: the floor tiles and bullet casings Deborah lugged back to the United States, her burnt kewpie doll and my crumbling plaster star, our marked-up maps, and Deborah’s archive of more than 2000 photographs taken between 2005 and 2008—traces of lived Palestinian lives, imbued with meanings far beyond their physical reality.

Among these objects is a CD mailer that reached me in Boston a year after we had stopped our search. For twelve years this small box lay on my desk unopened, buried among piles of mail, notes, and bills, its cardboard increasingly brittle, the return address faded to near illegibility. Postmarked Inverness, Scotland, I knew what it would contain, but only when I began revising this chapter that I finally cut through the sealing tape, and even then I hesitated to extract the CD. No, not now. Not yet, something in me said.

It’s hard to find words for that “something.” It had to do with an ache I feel whenever the Nakba comes up, shame about what my Israeli colleague, Shmulik, called “the original sin” of the state’s founding, and grief about utopian dreams gone awry. It’s a feeling that won’t let go, where the Palestinians’ loss of homelands challenged my love of a land that had also been my own home.

This CD was sure to touch a nerve. It was a record of a small Scottish group’s visit to the ruins of the Palestinian village of Bir’im, a group that welcomed me when I chanced on them in 2007. This was the only mail I could have conceivably gotten from Inverness. It would include the voice of Anis Shakour, the Palestinian lawyer from Haifa who guided the group through the village ruins. He was old enough in 1948 to remember his childhood’s Bir’im and kept track of the intricately linked community that is now scattered in Lebanon, Haifa, and the Israeli village of Jish.

It was my second visit to Bir’im when I met them, and by then I already knew something of Bir’im’s history—a legal case, not a battle. Together with another Christian Palestinian village, Iqrit, Bir’im had been in the news. Its residents had been ordered to evacuate temporarily, assured that the evacuation would be brief, just to let the army secure the border with Lebanon. They complied and yet were never allowed to return. The many lawsuits and appeals that followed, all the way up to Israel’s Supreme Court, were all decided in Bir’im’s favor to no avail. There were mass demonstrations, petitions, and publicity, but permission to return and rebuild was never granted.

Except for the church, standing intact in a grove of pines, most of the village has been demolished. Only fragments of buildings remain, close enough to one another to let one imagine the village as it used to be, even if only as a transparency hovering over the ruins: a free-standing wall with a doorway that leads to rubble; a courtyard where a self-sown fig tree breaks the paving; a house whose beams no longer support a roof; and the afternoon sun streaming through tall twin windows to illuminate a void that was once a room. I could imagine hearing a woman calling a neighbor, children playing in a courtyard, or a donkey’s hooves clomping on the cobblestones of narrow alleys that have since become impassable, choked by fallen masonry and scrub.

Anis was leading us through the rubble-choked alleys, pointing out who lived in each broken shell of a house. Each had been home to a family with children and grandparents and uncles and aunts, some on the mother’s side and some on the father’s, families that shared alleys and married into one another, each a repository of a genealogy and stories that were woven into its neighbors’ stories and genealogies. There was the house Anis’s great grandfather had built when he came from neighboring Khurfeish to repair Bir’im’s church; the house where Anis’ school friend Anton lived; and beyond it an uncle’s; and further yet another’s. Names and more names, each invoked as if to repopulate the ruins. We kept passing roofs that now gaped, cisterns clogged with rubble, walls that were barely standing, and further out, newly forested vistas.

Modern Israel is so near, I thought as I watched a distant car weaving in and out of the dark green forest heading for Israeli Dovev or kibbutz Bar’am. Beyond the lush carpet was Lebanon, mysterious in the fading afternoon light, unknown. The tour was almost over, I realized as Bir’im’s church came into view. Solid, cared for, and intact, it felt defiant, determined to last. The sanctuary’s windows were shuttered, and a large padlock had been placed on the front door. Near it, just to the right of a threshold worn smooth by the passing generations, stood the church’s cornerstone. Written was the word “FREEDOM,” painted in large yellow block letters.

This is how I had seen the church a year earlier and how I saw it when I approached the padlocked door with Anis and his Scottish visitors. It was also how I saw it a year later. Nothing much had changed. The same ruins, the same pine trees, and the same afternoon sun. Only this time the visitors happened to be Israeli and German youths enrolled in a yearlong course on the Holocaust and the Nakba. The church was still padlocked but in the fading light I could still make out the word “FREEDOM,” written on the cornerstone.